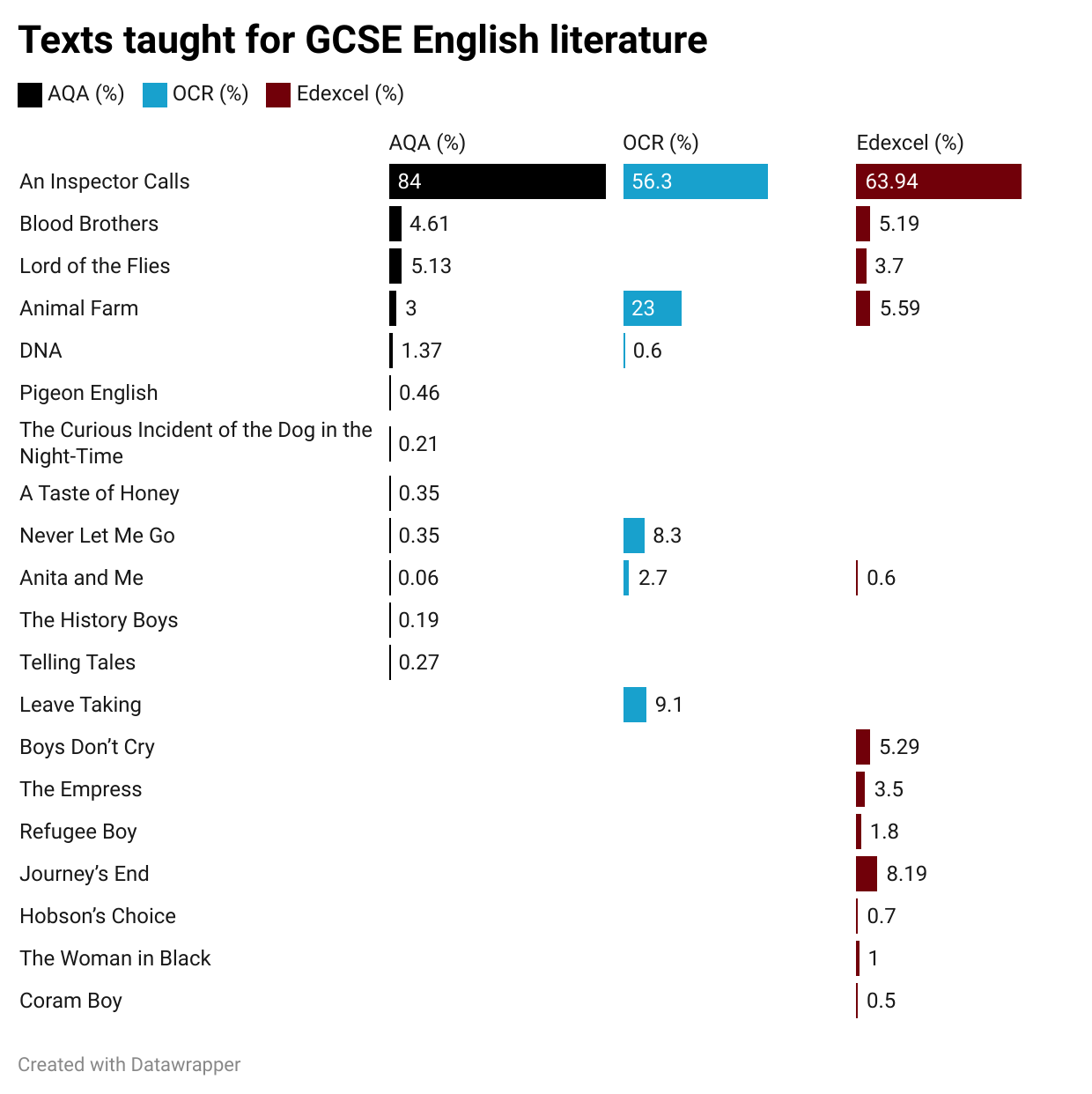

A recent TES article highlights the dominance of An Inspector Calls in the GCSE English literature curriculum, with high uptake across all major exam boards in June 2024: 84.00% of AQA students, 63.94% of Edexcel students, and 56.30% of OCR students studied the text.

This consistency may reflect inertia. The play’s familiarity, availability of teaching resources, and strong alignment with assessment criteria make it a reliable choice for teachers under pressure to deliver results. However, over reliance on this text signals potential stagnation in the GCSE English literature curriculum.

Other familiar texts, such as Blood Brothers, Lord of the Flies, and Animal Farm, maintain some shares. For instance, Animal Farm was selected by 23.00% of OCR students, 5.59% of Edexcel candidates, and 3.00% of those sitting AQA exams—and Blood Brothers has some uptake on Edexcel (5.19%) and AQA (4.61%). However, 9.1% of OCR candidates chose Jamaican playwright Winsome Pinnock’s Leave Taking. This suggests there is scope for a more varied curriculum if teachers and schools are supported. This idea is bolstered if we consider AQA’s comments in its submission of evidence to the current curriculum and assessment review:

“Difficult decisions need to be made about where content that increases diversity is mandated, and where teachers have autonomy to choose. […] Some of this is a symptom of what is delivered in classrooms. Despite having a range of texts by women on the specification, only 7% of students answer questions about novels or plays by a woman in our specifications because of teacher text choice. Despite our recent addition of works by three women of colour to our set text list in GCSE English Literature, most teachers of our specification deliver JB Priestley’s An Inspector Calls. […] The reasons for this could be due to familiarity, assumptions about examiner knowledge or preference, the time needed to acquire training and resources for other novels and plays, a lack of physical copies of the texts themselves, or a combination of these.”

Regarding support and resources, TES quote professor Robert Eaglestone, lead on educational policy at The English Association, who says: “If you’ve got 30 copies of An Inspector Calls already, a lot of schools can’t afford to buy 30 or 60 copies of a new play or novel.”

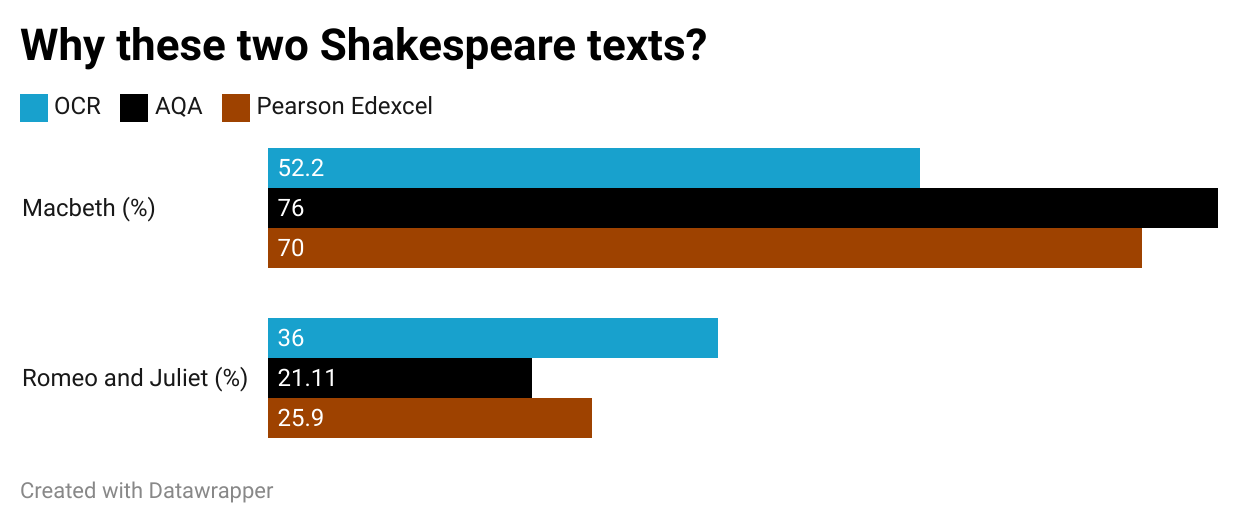

Turning to Shakespeare, options in GCSE English literature include The Merchant of Venice, The Tempest, Much Ado About Nothing and Julius Caesar. But two other texts predominate.

What drives classroom choices?

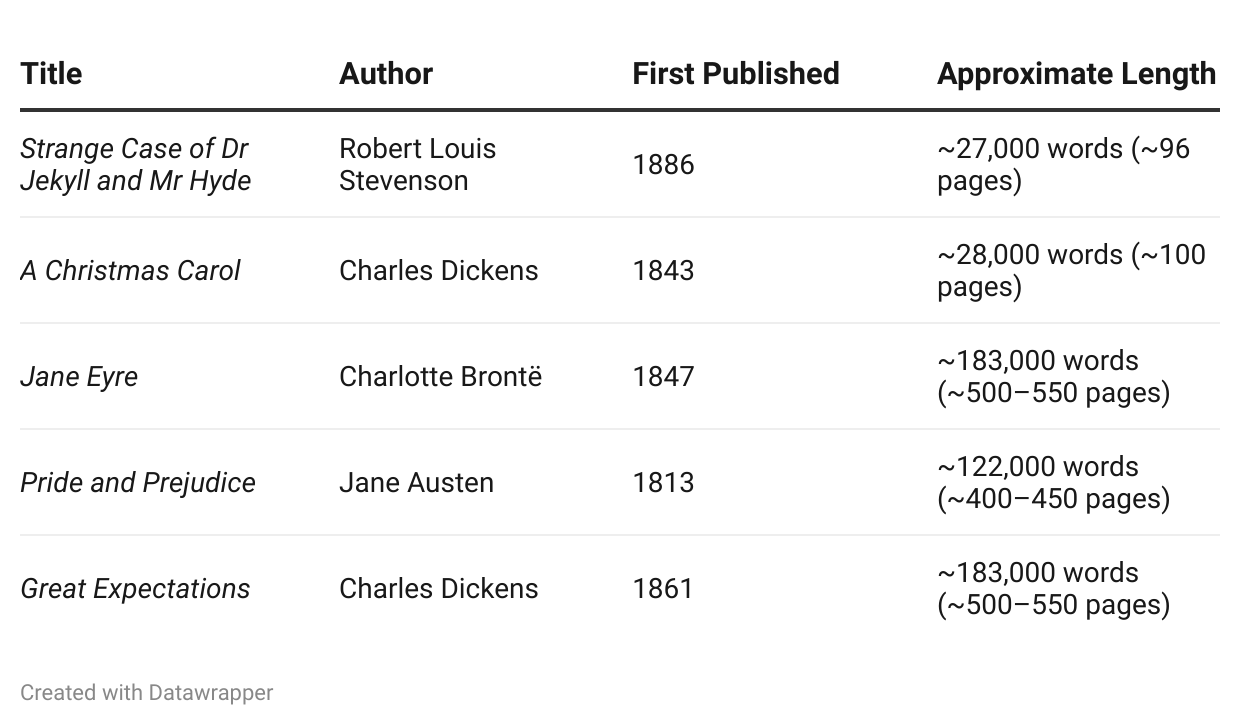

What might influence the choice of a 19th-century novel besides its literary qualities? The TES article mentions that Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and A Christmas Carol are most commonly picked across the three exam boards. Jane Eyre, Pride and Prejudice and Great Expectations were much less common. Why is this? Could the right-most column below have anything to do with it?

Studying a 400 or 500 page novel compared to a 100 page one is a significant choice in current teaching conditions. But to complicate the picture we should consider Shakespeare plays where choice may be influenced by word count in the case of Macbeth but by other factors with Romeo and Juliet.

Here, as AQA state, “familiarity, assumptions about examiner knowledge or preference, the time needed to acquire training and resources for other novels and plays, a lack of physical copies of the texts themselves, or a combination of these” may be the dominant factors affecting choice. Perceived accessibility of themes for young students and of media such as Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film may steer some teachers towards Romeo and Juliet, but so may cost constraints on schools and colleges that Eaglestone mentions, and the severe workload constraints on teachers who need time to prepare for a new text, create their own resources, plan lessons, and refine their teaching on the new work.

These patterns suggest that a small cluster of familiar, traditionally canonical texts dominate student experience, regardless of exam board. More contemporary or socially diverse offerings—particularly those introduced to diversify the curriculum—are present but rarely chosen. The figures raise questions about different kinds of systemic barriers stifling curriculum innovation.

Is the lack of variety due to absence of interest or relevance? Unlikely. Are structural limitations more probable? Limited school budgets, overworked staff, and risk-averse decision-making due to high stakes assessment may play a significant role.

What do you think?

Leave a comment